I briefly tried Samsung Galaxy XR at its launch event in New York last week, and I have mixed initial thoughts about the first Android XR headset.

Launched last night in the US & South Korea, Galaxy XR is priced at $1800, and its optional controllers are $250 extra, or $175 if you buy them with the headset before November 17.

Already, the Galaxy XR headset is backordered to November 4, while new orders for the Galaxy XR Controllers won’t ship until November 28.

The launch comes almost three years after Samsung first announced that it was working on a standalone XR headset, with Google handling much of the software and Qualcomm providing the chipset, and almost a year after it formally unveiled it as “Project Moohan” as Google revealed Android XR.

At its core, Galaxy XR is a high-end standalone headset with 4K micro-OLED displays, hand tracking, eye tracking, face tracking, an active depth sensor, and fully automatic motorized lens separation adjustment to match your interpupillary distance (IPD). You can read the detailed features and specifications of Galaxy XR here, and I strongly recommend you do so, but this article is about my brief experience actually using it.

Samsung Galaxy XR With Android XR Out Now For $1800, Controllers $250

Samsung Galaxy XR with Google’s Android XR is available now in the US & South Korea for $1800, and its controllers are $250 extra. Read the full specs and details here.

Samsung invited UploadVR to its embargoed launch event in New York last week, and we paid for our own flights and accommodation to attend it. I was in the audience for the on-stage presentation Samsung broadcast last night, and afterwards my colleague Ian Hamilton and I spoke to Google and Samsung representatives for hours as they used Galaxy XR directly in front of us, casting the headset’s view to a projector in the room full of journalists and influencers.

We ended the day with a very short hands-on demo where I used Galaxy XR myself for around 25 minutes, though it felt like even less. I’ll need far more time in the headset before I can bring you a more definitive assessment. But read on for my initial impressions based on my short time with Samsung Galaxy XR.

The Form Factor & Fit Matter

Many people have suggested that Galaxy XR is essentially an Android-ecosystem Apple Vision Pro for half the price. And while that’s broadly the product proposition here, the form factor is very different, and it’s important you understand how and why before buying it.

For starters, Galaxy XR has a rigid plastic strap that cradles the back of your head, like a Quest Elite Strap, offering balanced support. But it’s non-detachable, and this means you’re stuck with it for the lifetime of the headset. You can’t swap it out for a soft strap to lean back on a chair, sofa, or bed. If you’re interested in the idea of watching movies on a giant virtual screen, a pitched use case for both Vision Pro and Galaxy XR, you need to be aware of this. And if you’re interested in using the headset on a plane, for example, you’d find yourself bumping the back of the strap into the seat frequently. If you don’t need to use the headset in these scenarios, though, the rear strap design is all upside.

When it comes to the front of Galaxy XR, though, the differences are even more important to understand.

There are fundamentally two ways for a half-kilogram headset to attach to the front of your head: against your entire upper face, or just the top of your forehead.

In theory, the upper face approach, used in headsets like Apple Vision Pro and Meta Quest 3, distributes the pressure over a greater area. But this area also includes the sinuses under your lower forehead and cheeks, which are very sensitive to being crushed, and this is the cause of much of the discomfort associated with VR. It also blocks out your view of your periphery, with the exception of the odd open interface Meta released for Quest 3 last year.

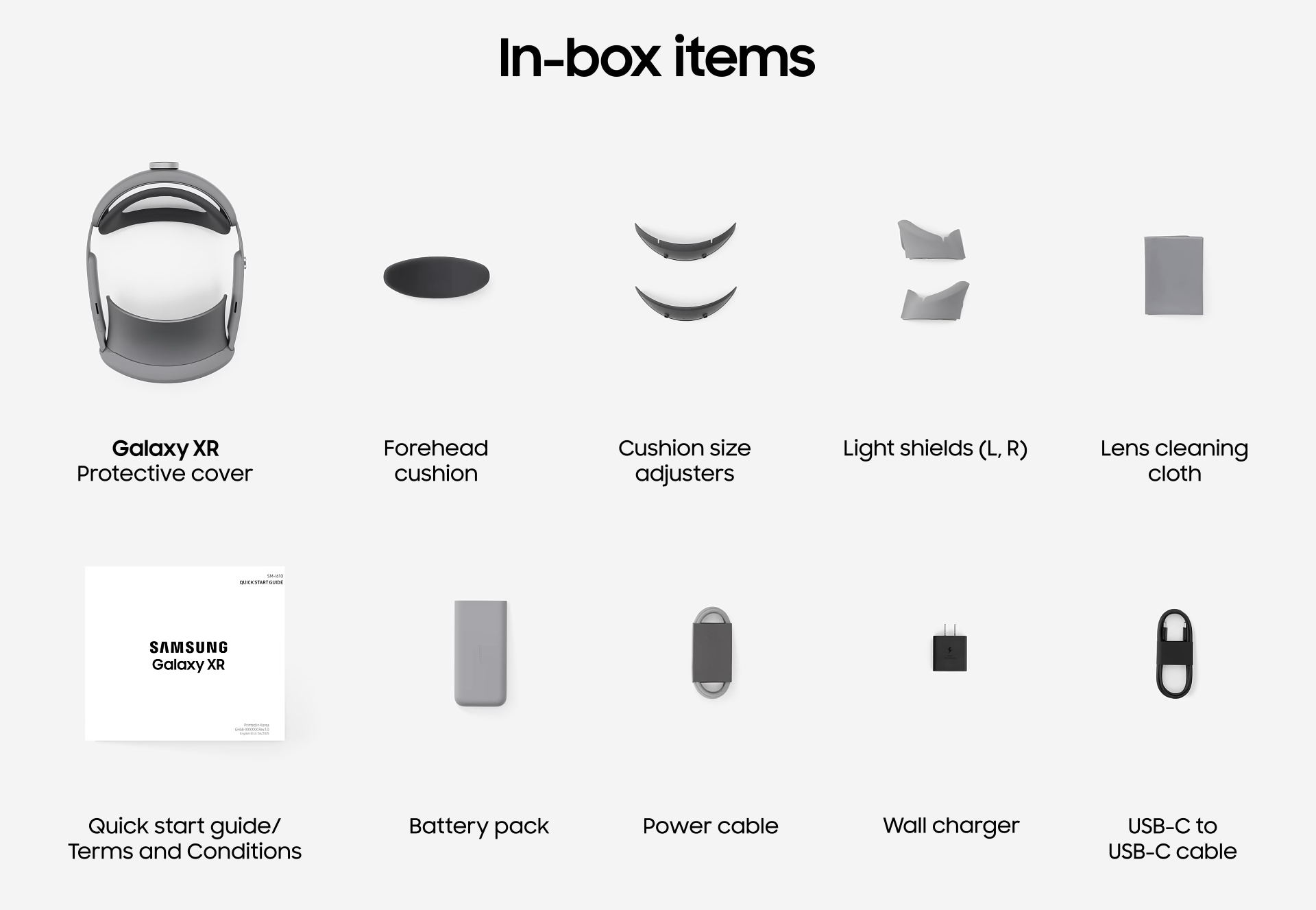

The alternate approach, an upper-forehead pad, is what Samsung Galaxy XR uses, like PlayStation VR2 and the discontinued Meta Quest Pro and HoloLens 2 headsets. This keeps the pressure off your sinuses, and makes the visor feel as if it’s floating in front of your face, rather than being attached, while also letting you see the real world below you and to the sides by default – there are optional side blockers for immersion in the box. The singular adjustment you make is to the dial at the rear, tightening or loosening the headset’s grip on your head.

Galaxy XR felt comfortable and light in my 25 minutes with it. But that simply is nowhere near enough time to tell you whether it would be comfortable for hours on end. What I can tell you is that its ergonomics feel very similar to Meta Quest Pro, except 200 grams lighter (Galaxy XR feels very light), and Quest Pro’s comfort was extremely divisive. How the forehead pad approach will feel for you will depend on the exact shape of your skull. Some people find the approach significantly more comfortable than any ski-goggle-style headsets, while others find it agonizingly painful.

Maybe someday someone will release an app that lets you scan the shape of your head to recommend whether a particular type of headset strap should suit it. In the meantime, I recommend trying to get a demo of Galaxy XR, if you’ve never used a headset with its ergonomics, before dropping $2000.

How That Affected What I Saw

My description so far describes how the strap design of Samsung Galaxy XR might limit how you can use the headset, how comfortable you feel, and how you see your surroundings by default. But it also affects how your eyes are aligned with the lenses.

To be clear, I’m not talking about horizontal alignment here. Galaxy XR has fully automatic IPD adjustment, guided by its eye tracking, with motorized lenses that shift sideways to match the horizontal separation of your eyes, which varies between people. This worked flawlessly for me. In fact, the process worked faster than Apple Vision Pro. But this solves for only one of three axes.

An issue with a forehead-mounted headset is that it can limit how close the lenses can get to your eyess laterally. To what degree, again, will depend on the exact shape of your skull. Headsets like Quest Pro and PS VR2 have a separate dial at the front to adjust the depth of the visor to your face, letting you bring the lenses closer to your eye, but Galaxy XR does not.

The result was that I wasn’t getting the full field of view, and nor the full binocular overlap, meaning I could see faint dark lines where the two lens views intersect. And worse, it induced a kind of perceived display brightness inconsistency, where areas of the lenses near the edges appeared to be darker. This is something I’ve seen before many times in headsets where my eyes aren’t close enough to the lenses. If Galaxy XR had a lens depth dial, I’d have used it. But it does not.

Days later, I found out that there are two forehead interface sizes in the box of Galaxy XR, and it’s possible I was just using the wrong one for my head. I was not informed of this before or during the demo.

Putting the lens depth issue aside, the displays of Galaxy XR are vibrant and incredibly sharp. They felt around on par with Apple Vision Pro, perhaps a tad sharper. As we’ve said before many times at UploadVR: 4K micro-OLEDs are the ultimate displays for headsets, and blow the 2K panels you find on mainstream headsets out of the water. A 2K LCD feels like looking at a screen. A 4K micro-OLED feels like looking at a virtual world. Once you try 4K micro-OLED, you can never truly go back. Galaxy XR is no exception to this reality.

Tracking & Passthrough

One of the first things I like to test when trying a new headset is its core XR technology.

Passthrough, your view of the real world, is hard to compare between headsets without using them in the same room and the exact same lighting, as all cameras are heavily affected by their environment. But my initial preliminary assessment is that Galaxy XR’s passthrough is the best on the market yet.

With the same 6.5 megapixel resolution, it felt as sharp as Apple Vision Pro, and the perspective and depth felt more correct, while it lacked any of the annoying warping distortion of Meta Quest 3.

Galaxy XR’s passthrough does, however, exhibit a similar blur as Apple Vision Pro when you turn your head. If you keep your head still, moving objects like your hands appear smooth, to be clear, and the latency feels extremely low. But if you rotate your head, there’s a distinct motion blur. As I covered in my Apple Vision Pro review, this is the opposite situation from Quest 3.

Testing Galaxy XR’s hand tracking (capture by Ian Hamilton).

Transitioning into a virtual home environment, which you can do at any time by double-tapping the capacitive touchpad on the side of Galaxy XR, I found the positional head tracking to be rock solid, even as I got up and walked around the room. In 2025, for a first-class tech company like Google at least, inside-out positional tracking via computer vision is essentially a solved problem.

Hand tracking, on the other hand, was more of a mixed bag. It’s low latency and has very little jitter, and quickly recovers from full occlusion. But it doesn’t handle overlapping your hands quite as well as Quest 3 or Apple Vision Pro, with noticeable jankiness, and when I tried moving my hands rapidly, the tracking constantly cut out, with the hands flickering in and out of existence. It wouldn’t be suitable for fast-motion games.

Meta has had years to refine its hand tracking, since shipping the feature as a software update for the original Oculus Quest, with 2.0, 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 updates all bringing significant improvements, including to handling fast motions. We’ll be closely following whether Google does the same for Android XR through 2026.

Unfortunately, I was not able to test Galaxy XR Controllers in-headset, so I can’t tell you about how well they do or don’t work. I did briefly hold them, though. They felt slightly cheap, and didn’t conform to my hands as well as Meta’s Touch Plus controllers. But I need to try them in XR.

A Note On The Battery

Just like Apple Vision Pro, Samsung Galaxy XR requires the included external tethered battery. And as such, everything I said about the tradeoffs of a tethered battery in my Apple Vision Pro review applies.

When I put on Galaxy XR, I had to consciously adjust the battery to a suitable position. And when I stood up, I had to put it in my pocket and move my arm in front of the cable. It’s an added friction that crops up even in a 25 minute demo, and one that you need to be aware of if you’re coming from a headset with a built-in battery, or considering getting your first-ever headset.

In contrast, it’s refreshingly convenient to pick up a Meta Quest headset and just put it on your head, with no thought for cables or batteries needed.

How annoying an external battery is will come down to personal preference. Some people couldn’t care less. But I’d like to once again quote Oculus executive Jason Rubin in our 2019 interview with him, when we asked whether his company was considering a tethered portable compute model:

“That’s a model we’ve definitely explored. There’s a lot of upsides to it, like visually having the smaller glasses on your head, big advantage. Battery, keeping the weight away, the heat away from the screen, being able to separate battery. All of that is great.

The problem is when you do it, cause we’ve tried it, you have a wire. And you don’t ever forget that wire.“

Of course, a lot has changed in six years, and our sources suggest Meta plans a tethered puck for its next headset too. But it remains to be seen which approach to the battery consumers will choose in the long run.

Performance & Android XR

The demo I had was nowhere near long enough to assess an entirely new XR platform, so I’m going to avoid making sweeping conclusions here.

What I can tell you is that Android XR broadly feels like a crossover between Apple’s visionOS and Meta’s Horizon OS, and on Galaxy XR it felt incredibly snappy. I could open 2D or immersive apps and navigate around the system menus without any visible hitch in framerate. Performance was noticeably smoother than what I’m used to with Meta Quest 3. But I didn’t have time to really push it to its limit, and unlike with Meta’s Horizon OS, in Google’s Android XR you can’t bring up windows while still inside an immersive experience.

On paper, Galaxy XR’s XR2+ Gen 2 chipset is only around 20% more powerful than the one in Quest 3, but Galaxy XR has a few other tricks up its sleeve, including twice the RAM (16GB), eye-tracked foveated rendering, and a default refresh rate of 72Hz, easier to maintain than Quest 3’s default 90Hz. Some of it may also be down to software. Google, after all, is the company that makes Android itself, while Meta is forking it and isn’t exactly known for its software quality.

Google Maps immersive mode on Android XR

That 72Hz refresh rate does come with a tradeoff, though. In Google Maps immersive mode, for example, when very bright content was being displayed at the edge of the lenses I could see a faint flickering effect. This is a well-known issue with low-persistence displays if you drive them below 90Hz. And again – a common theme of this article – varies between individuals.

Speaking of Google Maps immersive mode, it’s essentially PC VR’s Google Earth VR officially ported to standalone VR for the first time. On Galaxy XR’s 4K micro-OLED displays it looks and feels incredible, and this is how I want to plan trips from now on. Its immersive Gaussian splats of select locations were cool to try, too, but significantly lower quality than Meta’s Horizon Hyperscape.

Google Photos with AI 3D synthesis on Android XR

Another Google feature that impressed me was in Photos. While other headsets like Apple Vision Pro and Pico 4 Ultra already let you convert 2D photos into 3D, Android XR goes a step further by allowing this for videos too. It’s remarkable how quickly it works. Like many Google features, it’s server-side, so if you’re opposed to that for privacy reasons, you’ll miss out. But it was remarkable to see a 2D video turn into 3D so quickly, in front of my eyes.

The strangest thing about Android XR is that by default, it doesn’t use the gaze-and-pinch interaction system introduced by Apple Vision Pro. Instead, you point with your hands as you would on Quest 3. Eye tracking is always active for foveated rendering, but gaze-and-pinch is an option, off by default. I enabled it in Settings, though, and found it to work well. I’m very puzzled as to why it’s not the default, as my almost two years of time using Apple Vision Pro has me unshakeably convinced that it’s the future default input system for all of XR.

Conclusions

My time with Samsung Galaxy XR and Android XR was frustratingly short, and this article documents only my very initial impressions.

Galaxy XR delivers the magic of 4K micro-OLED in a standalone form factor at half the price of Apple Vision Pro and the Android XR platform from Google seemed well-made in my time with it, and is a potential serious threat to Meta in the long term.

But Galaxy XR’s form factor, while perhaps similar at first glance of a render, is fundamentally different than Vision Pro (and Quest 3), and my experience with similar headsets tells me that its comfort might vary significantly between individuals.

Samsung did not provide UploadVR with a review unit, but we’ve now ordered our own Galaxy XR at our own expense, and aim to bring you a review next month after we get it.