of this series, we will talk about deep learning.

And when people talk about deep learning, we immediately think of these images of deep neural networks architectures, with many layers, neurons, and parameters.

In practice, the real shift introduced by deep learning is elsewhere.

It is about learning data representations.

In this article, we focus on text embeddings, explain their role in the machine learning landscape, and show how they can be understood and explored in Excel.

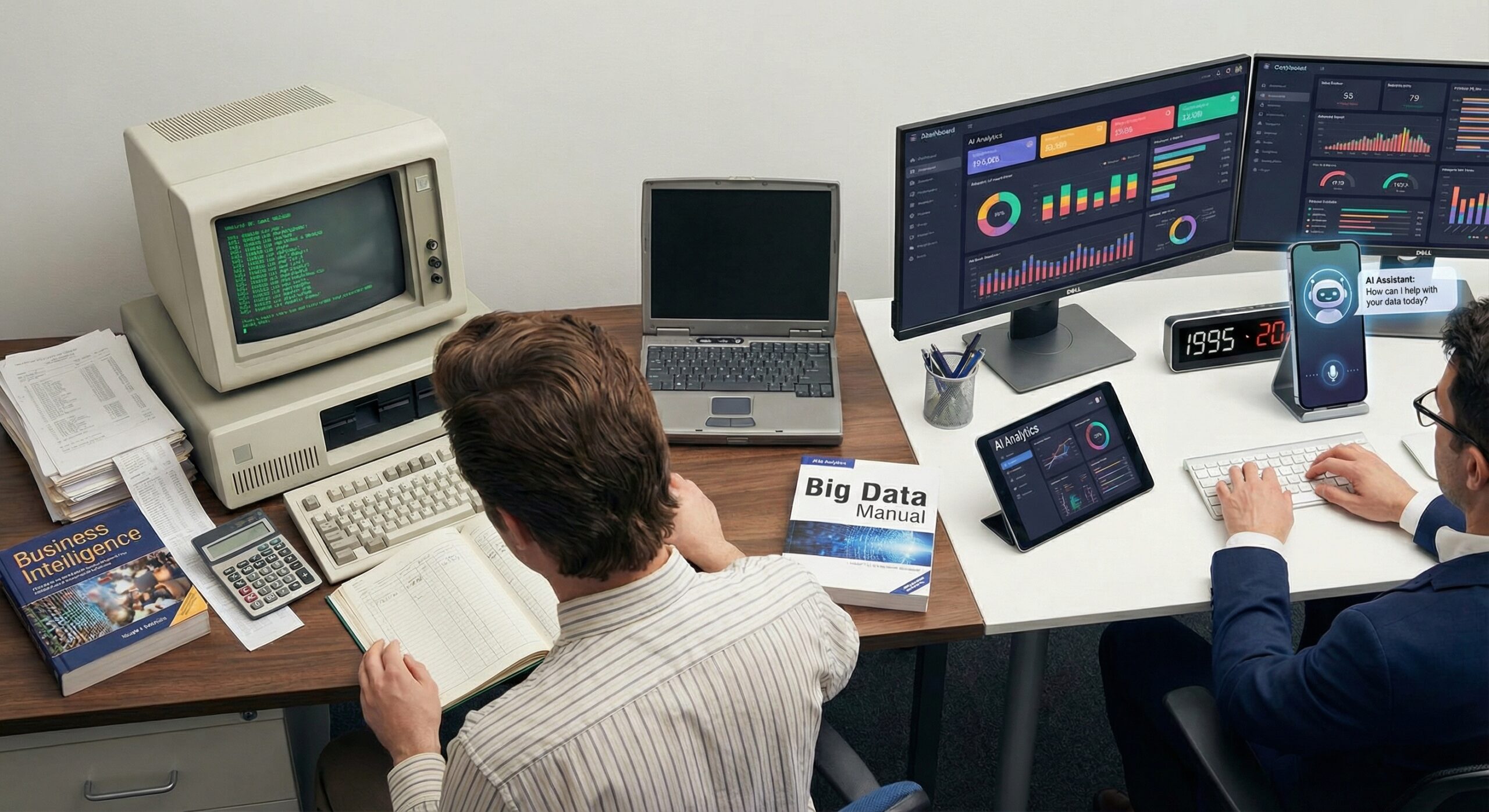

1. Classic Machine earning vs. Deep learning

We will discuss, in this part, why embedding is introduced.

1.1 Where does deep learning fit?

To understand embeddings, we first need to clarify the place of deep learning.

We will use the term classic machine learning to describe methods that do not rely on deep architectures.

All the previous articles deal with classic machine learning, that can be described in two complementary ways.

Learning paradigms

- Supervised learning

- Unsupervised learning

Model families

- Distance-based models

- Tree-based models

- Weight-based models

Across this series, we have already studied the learning algorithms behind these models. In particular, we have seen that gradient descent applies to all weight-based models, from linear regression to neural networks.

Deep learning is often reduced to neural networks with many layers.

But this explanation is incomplete.

From an optimization point of view, deep learning does not introduce a new learning rule.

So what does it introduce?

1.2 Deep learning as data representation learning

Deep learning is about how features are created.

Instead of manually designing features, deep learning learns representations automatically, often through multiple successive transformations.

This also raises an important conceptual question:

Where is the boundary between feature engineering and model learning?

Some examples make this clearer:

- Polynomial regression is still a linear model, but the features are polynomial

- Kernel methods project data into a high-dimensional feature space

- Density-based methods implicitly transform the data before learning

Deep learning continues this idea, but at scale.

From this perspective, deep learning belongs to:

- the feature engineering philosophy, for representation

- the weight-based model family, for learning

1.3 Images and convolutional neural networks

Images are represented as pixels.

From a technical point of view, image data is already numerical and structured: a grid of numbers. However, the information contained in these pixels is not structured in a way that classical models can easily exploit.

Pixels do not explicitly encode: edges, shapes, textures, or objects.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are designed to create information from pixels. They apply filters to detect local patterns, then progressively combine them into higher-level representations.

I have published a this article showing how CNNs can be implemented in Excel to make this process explicit.

For images, the challenge is not to make the data numerical, but to extract meaningful representations from already numerical data.

1.4 Text data: a different problem

Text presents a fundamentally different challenge.

Unlike images, text is not numerical by nature.

Before modeling context or order, the first problem is more basic:

How do we represent words numerically?

Creating a numerical representation for text the first step.

In deep learning for text, this step is handled by embeddings.

Embeddings transform discrete symbols (words) into vectors that models can work with. Once embeddings exist, we can then model: context, order and relationships between words.

In this article, we focus on this first and essential step:

how embeddings create numerical representations for text, and how this process can be explored in Excel.

2. Two ways to learn text embeddings

In this article, we will use the IMDB movie reviews dataset to illustrate both approaches. The dataset is distributed under the Apache License 2.0.

There are two main ways to learn embeddings for text, and we will do both with this dataset:

- supervised: we will create embeddings to predict the sentiment

- unsupervised or self-supervised: we will use word2vec algorithm

In both cases, the goal is the same:

to transform words into numerical vectors that can be used by machine learning models.

Before comparing these two approaches, we first need to clarify what embeddings are and how they relate to classic machine learning.

2.1 Embeddings and classic machine learning

In classic machine learning, categorical data is usually handled with:

- label encoding, which assigns fixed integers but introduces artificial order

- one-hot encoding, which removes order but produces high-dimensional sparse vectors

How they can be used depend on the nature of the models.

Distance-based models cannot effectively use one-hot encoding, because all categories end up being equally distant from each other. Label encoding could work only if we can attribute meaningful numerical values for the categories, which is generally not the case in classic models.

Weight-based models can use one-hot encoding, because the model learns a weight for each category. In contrast, with label encoding, the numerical values are fixed and cannot be adjusted to represent meaningful relationships.

Tree-based models treat all variables as categorical splits rather than numerical magnitudes, which makes label encoding acceptable in practice. However, most implementations, including scikit-learn, still require numerical inputs. As a result, categories must be converted to numbers, either through label encoding or one-hot encoding. If the numerical values carried semantic meaning, this would again be beneficial.

Overall, this highlights a limitation of classic approaches:

category values are fixed and not learned.

Embeddings extend this idea by learning the representation itself.

Each word is associated with a trainable vector, turning the representation of categories into a learning problem rather than a preprocessing step.

2.2 Supervised embeddings

In supervised learning, embeddings are learned as part of a prediction task.

For example, the IMDB dataset has labels about the in sentiment analysis. So we can create a very simple architecture:

In our case, we can use a very simple architecture: each word is mapped to a one-dimensional embedding

This is possible because the objective is binary sentiment classification.

Once training is complete, we can export the embeddings and explore them in Excel.

When plotting the embeddings on the x-axis and word frequency on the y-axis, a clear pattern appears:

- positive values are associated with words such as excellent or wonderful,

- negative values are associated with words such as worst or waste

Depending on the initialization, the sign can be inverted, since the logistic regression layer also has parameters that influence the final prediction.

Finally, in Excel, we reconstruct the full pipeline that corresponds to the architecture we define early.

Input column

The input text (a review) is cut into words, and each row corresponds to one word.

Embedding search

Using a lookup function, the embedding value associated with each word is retrieved from the embedding table learned during training.

Global average

The global average embedding is computed by averaging the embeddings of all words seen so far. This corresponds to a very simple sentence representation: the mean of word vectors.

Probability prediction

The averaged embedding is then passed through a logistic function to produce a sentiment probability.

What we observe

- Words with strongly positive embeddings (for example excellent, love, fun) push the average upward.

- Words with strongly negative embeddings (for example worst, horrible, waste) pull the average downward.

- Neutral or weakly weighted words have little influence.

As more words are added, the global average embedding stabilizes, and the sentiment prediction becomes more confident.

2.3 Word2Vec: embeddings from co-occurrence

In Word2Vec, similarity does not mean that two words have the same meaning.

It means that they appear in similar contexts.

Word2Vec learns word embeddings by looking at which words tend to co-occur within a fixed window in the text. Two words are considered similar if they often appear around the same neighboring words, even if their meanings are opposite.

As shown in the Excel sheet below, we compute the cosine similarity for the word good and retrieve the most similar words.

From the model’s perspective, the surrounding words are almost identical. The only thing that changes is the adjective itself.

As a result, Word2Vec learns that “good” and “bad” play a similar role in language, even though their meanings are opposite.

So, Word2Vec captures distributional similarity, not semantic polarity.

A useful way to think about it is:

Words are close if they are used in the same places.

2.4 How embeddings are used

In modern systems such as RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), embeddings are often used to retrieve documents or passages for question answering.

However, this approach has limitations.

Most commonly used embeddings are trained in a self-supervised way, based on co-occurrence or contextual prediction objectives. As a result, they capture general language similarity, not task-specific meaning.

This means that:

- embeddings may retrieve text that is linguistically similar but not relevant

- semantic proximity does not guarantee answer correctness

Other embedding strategies can be used, including task-adapted or supervised embeddings, but they often remain self-supervised at their core.

Understanding how embeddings are created, what they encode, and what they do not encode is therefore essential before using them in downstream systems such as RAG.

Conclusion

Embeddings are learned numerical representations of words that make similarity measurable.

Whether learned through supervision or through co-occurrence, embeddings map words to vectors based on how they are used in data. By exporting them to Excel, we can inspect these representations directly, compute similarities, and understand what they capture and what they do not.

This makes embeddings less mysterious and clarifies their role as a foundation for more complex systems such as retrieval or RAG.

Source link

#Machine #Learning #Advent #Calendar #Day #Embeddings #Excel