A new research paper published by Stanford VR researchers in the top social science journal combs through decades of study and suggests five ground truths about the medium.

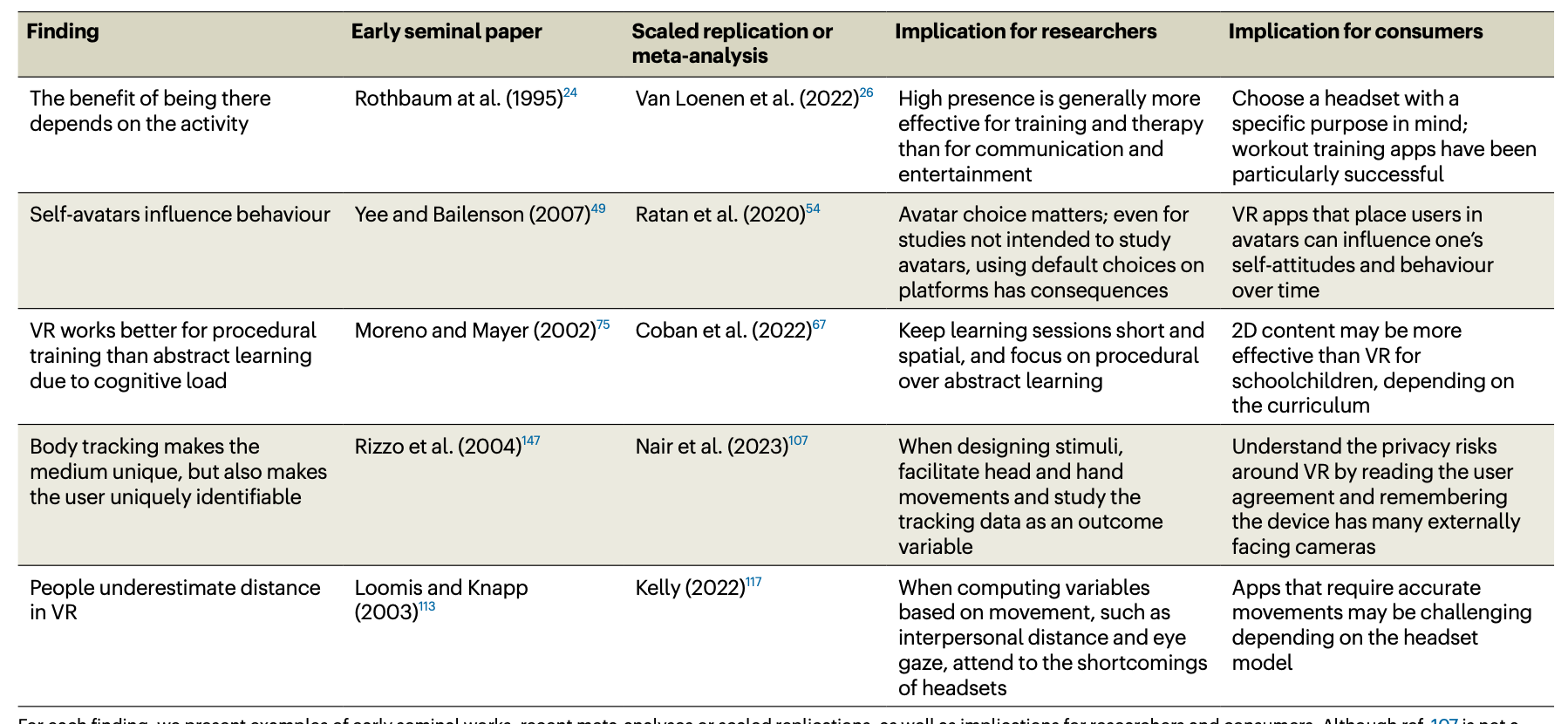

The chart below from the paper in Nature Human Behavior outlines the implications for researchers and consumers of key findings from decades of psychological research in VR.

Regular readers will be familiar with some of these ideas, but for those reaching this page through a VR-initiated friend who sent it to them? It’s a lot just to realize the Meta Quest 3s at $300 and Vision Pro at $3500 are fundamentally the same core technology – a VR headset – and they are part of a now-decades-long trend steadily marching toward mainstream adoption.

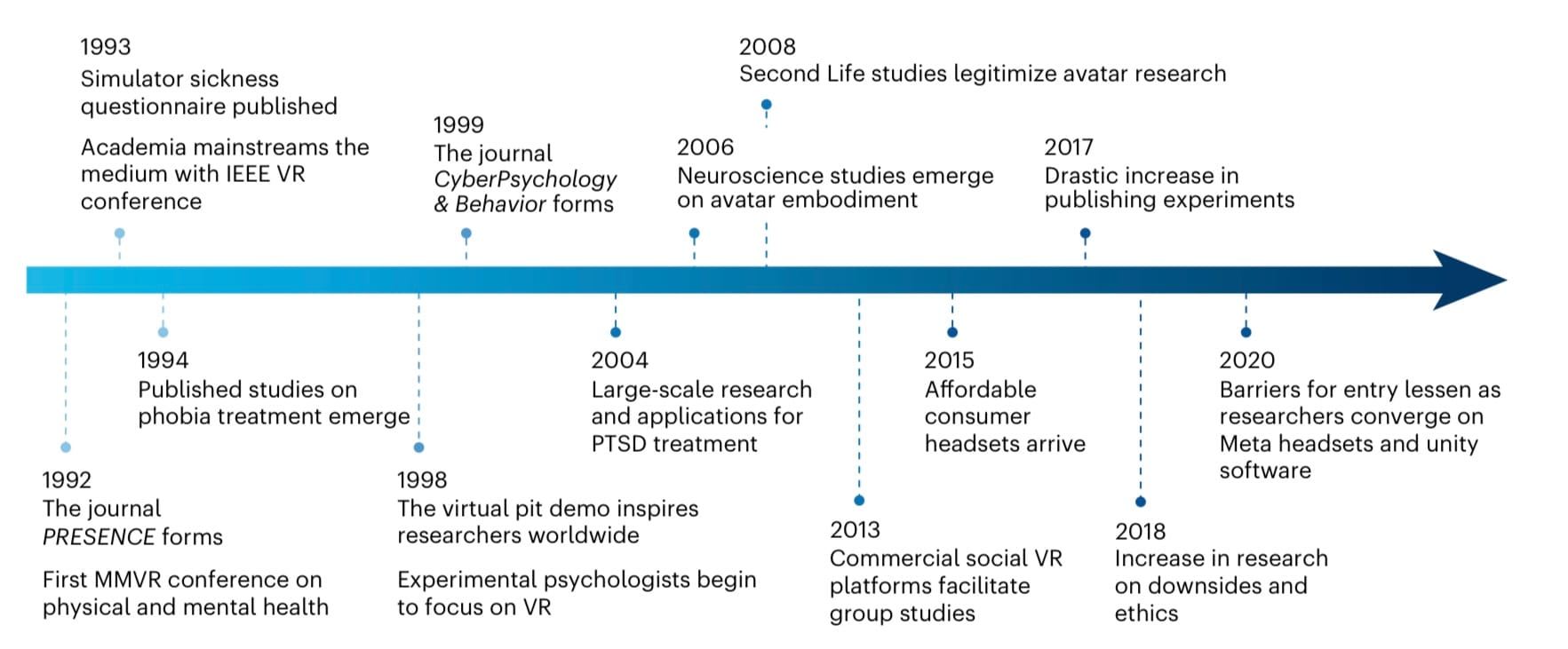

The timeline from the paper embedded below outlines the journey as it relates to VR research.

Below I’ve listed the implications for consumers of the five key findings covered by the paper:

- “Choose a headset with a specific purpose in mind; workout training apps have been particularly successful”

- “VR apps that place users in avatars can influence one’s self-attitudes and behavior over time”

- 2D content may be more effective than VR for schoolchildren, depending on the curriculum”

- “Understand the privacy risks around VR by reading the user agreement and remembering the device has many externally facing cameras”

- “Apps that require accurate movements may be challenging depending on the headset model”

You can read the full paper on Stanford’s website, which also suggests a need for longitudinal work and study of VR’s downsides.

What Is VR Used For?

The paper also uses the word “DICE” to help remember four categories of VR experience “we primarily use VR for dangerous, impossible, counterproductive or expensive experiences that are not easy to implement in the real world,” echoing a line from Bailenson’s 2018 book “Experience On Demand”.

“Training firefighters, rehabilitating stroke victims, learning art history via sculpture museums, and having a visceral, perceptual experience of the Earth’s future to understand climate change, for example, all fit squarely in DICE,” the paper explains. “Alternatively, one does not necessarily need to don a headset to check email, watch television and conduct general office work. Such applications work better on 2D screens. By not putting such use cases needlessly into VR, society can avoid some of its challenges.”

“One does not necessarily need to don a headset to check email, watch television and conduct general office work. Such applications work better on 2D screens. By not putting such use cases needlessly into VR, society can avoid some of its challenges.”

This is a fascinating framing for thinking about the difference between going to VR because you want to and going to VR because you have to.

I use Quest 3 because I easily play mini golf and meet with my coworker to talk about the future in front of hundreds of people each week. I like to use my Vision Pro because I can go to the moon to start my day, and I can bring up the earth as a tiny globe and zoom right down to street level. The experience is either downright impossible or at least too expensive for the real world. At that point, accessing my email and TV and work in VR too just keeps me on the moon for longer.

If you’re interested in diving deeper into why people use VR, and what it might be used for in the future, I recommend starting with my write-up about the twins who stay connected playing Walkabout Mini Golf and continue on to the walkable Holodeck in Texas. And be sure to check out the VR Download on Thursdays where we cover the very latest.

Source link

#Stanford #Researchers #Suggest #Canonical #Findings