Linear Regression, finally!

For Day 11, I waited many days to present this model. It marks the beginning of a new journey in this “Advent Calendar“.

Until now, we mostly looked at models based on distances, neighbors, or local density. As you may know, for tabular data, decision trees, especially ensembles of decision trees, are very performant.

But starting today, we switch to another point of view: the weighted approach.

Linear Regression is our first step into this world.

It looks simple, but it introduces the core ingredients of modern ML: loss functions, gradients, optimization, scaling, collinearity, and interpretation of coefficients.

Now, when I say, Linear Regression, I mean Ordinary Least Square Linear Regression. As we progress through this “Advent Calendar” and explore related models, you will see why it is important to specify this, because the name “linear regression” can be confusing.

Some people say that Linear Regression is not machine learning.

Their argument is that machine learning is a “new” field, while Linear Regression existed long before, so it cannot be considered ML.

This is misleading.

Linear Regression fits perfectly within machine learning because:

- it learns parameters from data,

- it minimizes a loss function,

- it makes predictions on new data.

In other words, Linear Regression is one of the oldest models, but also one of the most fundamental in machine learning.

This is the approach used in:

- Linear Regression,

- Logistic Regression,

- and, later, Neural Networks and LLMs.

For deep learning, this weighted, gradient-based approach is the one that is used everywhere.

And in modern LLMs, we are no longer talking about a few parameters. We are talking about billions of weights.

In this article, our Linear Regression model has exactly 2 weights.

A slope and an intercept.

That is all.

But we have to begin somewhere, right?

And here are a few questions you can keep in mind as we progress through this article, and in the ones to come.

- We will try to interpret the model. With one feature, y=ax+b, everyone knows that a is the slope and b is the intercept. But how do we interpret the coefficients where there are 10, 100 or more features?

- Why is collinearity between features such a problem for linear regression? And how can we do to solve this issue?

- Is scaling important for linear regression?

- Can Linear regression be overfitted?

- And how are the other models of this weighted familly (Logistic Regression, SVM, Neural Networks, Ridge, Lasso, etc.), all connected to the same underlying ideas?

These questions form the thread of this article and will naturally lead us toward future topics in the “Advent Calendar”.

Understanding the Trend line in Excel

Starting with a Simple Dataset

Let us begin with a very simple dataset that I generated with one feature.

In the graph below, you can see the feature variable x on the horizontal axis and the target variable y on the vertical axis.

The goal of Linear Regression is to find two numbers, a and b, such that we can write the relationship:

y=a x +b

Once we know a and b, this equation becomes our model.

Creating the Trend Line in Excel

In Google Sheets or Excel, you can simply add a trend line to visualize the best linear fit.

That already gives you the result of Linear Regression.

But the purpose of this article is to compute these coefficients ourselves.

If we want to use the model to make predictions, we need to implement it directly.

Introducing Weights and the Cost Function

A Note on Weight-Based Models

This is the first time in the Advent Calendar that we introduce weights.

Models that learn weights are often called parametric discriminant models.

Why discriminant?

Because they learn a rule that directly separates or predicts, without modeling how the data was generated.

Before this chapter, we already saw models that had parameters, but they were not discriminant, they were generative.

Let us recap quickly.

- Decision Trees use splits, or rules, and so there are no weights to learn. So they are non-parametric models.

- k-NN is not a model. It keeps the whole dataset and uses distances at prediction time.

However, when we move from Euclidean distance to Mahalanobis distance, something interesting happens…

LDA and QDA do estimate parameters:

- means of each class

- covariance matrices

- priors

These are real parameters, but they are not weights.

These models are generative because they model the density of each class, and then use it to make predictions.

So even though they are parametric, they do not belong to the weight-based family.

And as you can see, these are all classifiers, and they estimate parameters for each class.

Linear Regression is our first example of a model that learns weights to build a prediction.

This is the beginning of a new family in the Advent Calendar:

models that rely on weights + a loss function to make predictions.

The Cost Function

How can we obtain the parameters a and b?

Well, the optimal values for a and b are those minimizing the cost function, which is the Squared Error of the model.

So for each data point, we can calculate the Squared Error.

Squared Error = (prediction-real value)²=(a*x+b-real value)²

Then we can calculate the MSE, or Mean Squared Error.

As we can see in Excel, the trendline gives us the optimal coefficients. If you manually change these values, even slightly, the MSE will increase.

This is exactly what “optimal” means here: any other combination of a and b makes the error worse.

The classic closed-form solution

Now that we know what the model is, and what it means to minimize the squared error, we can finally answer the key question:

How do we compute the two coefficients of Linear Regression, the slope a and the intercept b?

There are two ways to do it:

- the exact algebraic solution, known as the closed-form solution,

- or gradient descent, which we will explore just after.

If we take the definition of the MSE and differentiate it with respect to a and b, something beautiful happens: everything simplifies into two very compact formulas.

These formulas only use:

- the average of x and y,

- how x varies (its variance),

- and how x and y vary together (their covariance).

So even without knowing any calculus, and with only basic spreadsheet functions, we can reproduce the exact solution used in statistics textbooks.

How to interpret the coefficients

For one feature, interpretation is straightforward and intuitive:

The slope a

It tells us how much y changes when x increases by one unit.

If the slope is 1.2, it means:

“when x goes up by 1, the model expects y to go up by about 1.2.”

The intercept b

It is the predicted value of y when x = 0.

Often, x = 0 does not exist in the real context of the data, so the intercept is not always meaningful by itself.

Its role is mostly to place the line correctly to match the center of the data.

This is usually how Linear Regression is taught:

a slope, an intercept, and a straight line.

With one feature, interpretation is easy.

With two, still manageable.

But as soon as we start adding many features, it becomes more difficult.

Tomorrow, we will discuss further about the interpretation.

Today, we will do the gradient descent.

Gradient Descent, Step by Step

After seeing the classic algebraic solution for Linear Regression, we can now explore the other essential tool behind modern machine learning: optimization.

The workhorse of optimization is Gradient Descent.

Understanding it on a very simple example makes the logic much clearer once we apply it to Linear Regression.

A Gentle Warm-Up: Gradient Descent on a Single Variable

Before implementing the gradient descent for the Linear Regression, we can first do it for a simple function: (x-2)^2.

Everyone knows the minimum is at x=2.

But let us pretend we do not know that, and let the algorithm discover it by itself.

The idea is to find the minimum of this function using the following process:

- First, we randomly choose an initial value.

- Then for each step, we calculate the value of the derivative function df (for this x value): df(x)

- And the next value of x is obtained by subtracting the value of derivative multiplied by a step size: x = x – step_size*df(x)

You can modify the two parameters of the gradient descent: the initial value of x and the step size.

Yes, even with 100, or 1000. That’s quite surprising to see, how well it works.

But, in some cases, the gradient descent will not work. For example, if the step size is too big, the x value can explode.

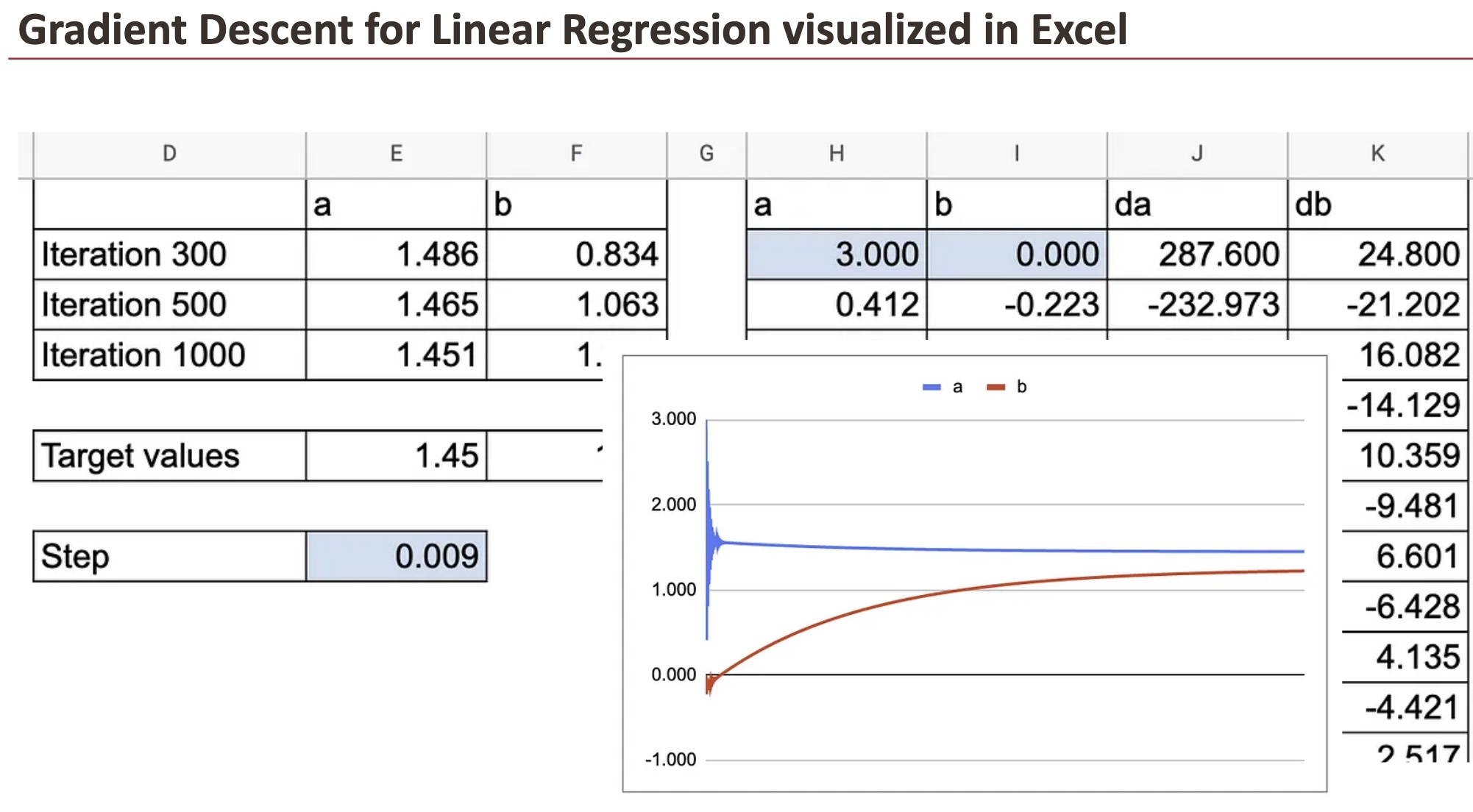

Gradient descent for linear regression

The principle of the gradient descent algorithm is the same for linear regression: we have to calculate the partial derivatives of the cost function with respect to the parameters a and b. Let’s note them as da and db.

Squared Error = (prediction-real value)²=(a*x+b-real value)²

da=2(a*x+b-real value)*x

db=2(a*x+b-real value)

And then, we can do the updates of the coefficients.

With this tiny update, step by step, the optimal value will be found after a few interations.

In the following graph, you can see how a and b converge towards the target value.

We can also see all the details of y hat, residuals and the partial derivatives.

We can fully appreciate the beauty of gradient descent, visualized in Excel.

For these two coefficients, we can observe how quick the convergence is.

Now, in practice, we have many observations and this should be done for each data point. That’s where things become crazy in Google Sheet. So, we use only 10 data points.

You will see that I first created a sheet with long formulas to calculate da and db, which contain the sum of the derivatives of all the observations. Then I created another sheet to show all the details.

Categorical Features in Linear Regression

Before concluding, there is one last important idea to introduce:

how a weight-based model like Linear Regression handles categorical features.

This topic is essential because it shows a fundamental difference between the models we studied earlier (like k-NN) and the weighted models we are entering now.

Why distance-based models struggle with categories

In the first part of this Advent Calendar, we used distance-based models such as K-NN, DBSCAN, and LOF.

But these models rely entirely on measuring distances between points.

For categorical features, this becomes impossible:

- a category encoded as 0 or 1 has no quantitative meaning

- the numerical scale is arbitrary,

- Euclidean distance cannot capture category differences.

This is why k-NN cannot handle categories correctly without heavy preprocessing.

Weight-based models solve the problem differently

Linear Regression does not compare distances.

It learns weights.

To include a categorical variable in a weight-based model, we use one-hot encoding, the most common approach.

Each category becomes its own feature, and the model simply learns one weight per category.

Why this works so well

Once encoded:

- the scale problem disappears (everything is 0 or 1),

- each category receives an interpretable weight,

- the model can adjust its prediction depending on the group

A simple two-category example

When there are only two categories (0 and 1), the model becomes extremely simple:

- one value is used when x=0,

- another when x=1.

One-hot encoding is not even necessary:

the numeric encoding already works because Linear Regression will learn the appropriate difference between the two groups.

Gradient Descent still works

Even with categorical features, Gradient Descent works exactly as usual.

The algorithm only manipulates numbers, so the update rules for a and b are identical.

In the spreadsheet, you can see the parameters converge smoothly, just like with numerical data.

However, in this specific two-category case, we also know that a closed-form formula exists: Linear Regression essentially computes two group averages and the difference between them.

Conclusion

Linear Regression may look simple, but it introduces almost everything that modern machine learning relies on.

With just two parameters, a slope and an intercept, it teaches us:

- how to define a cost function,

- how to find optimal parameters, numerically,

- and how optimization behaves when we adjust learning rates or initial values.

The closed-form solution shows the elegance of the mathematics.

Gradient Descent shows the mechanics behind the scenes.

Together, they form the foundation of the “weighted + loss function” family that includes Logistic Regression, SVM, Neural Networks, and even today’s LLMs.

New Paths Ahead

You may think Linear Regression is simple, but with its foundations now clear, you can extend it, refine it, and reinterpret it through many different perspectives:

- Change the loss function

Replace squared error with logistic loss, hinge loss, or other functions, and new models appear. - Move to classification

Linear Regression itself can separate two classes (0 and 1), but more robust versions lead to Logistic Regression and SVM. And what about multiclass classification? - Model nonlinearity

Through polynomial features or kernels, linear models suddenly become nonlinear in the original space. - Scale to many features

Interpretation becomes harder, regularization becomes essential, and new numerical challenges appear. - Primal vs dual

Linear models can be written in two ways. The primal view learns the weights directly. The dual view rewrites everything using dot products between data points. - Understand modern ML

Gradient Descent, and its variants, are the core of neural networks and large language models.

What we learned here with two parameters generalizes to billions.

Everything in this article stays within the boundaries of Linear Regression, yet it prepares the ground for an entire family of future models.

Day after day, the Advent Calendar will show how all these ideas connect.

Source link

#Machine #Learning #Advent #Calendar #Day #Linear #Regression #Excel